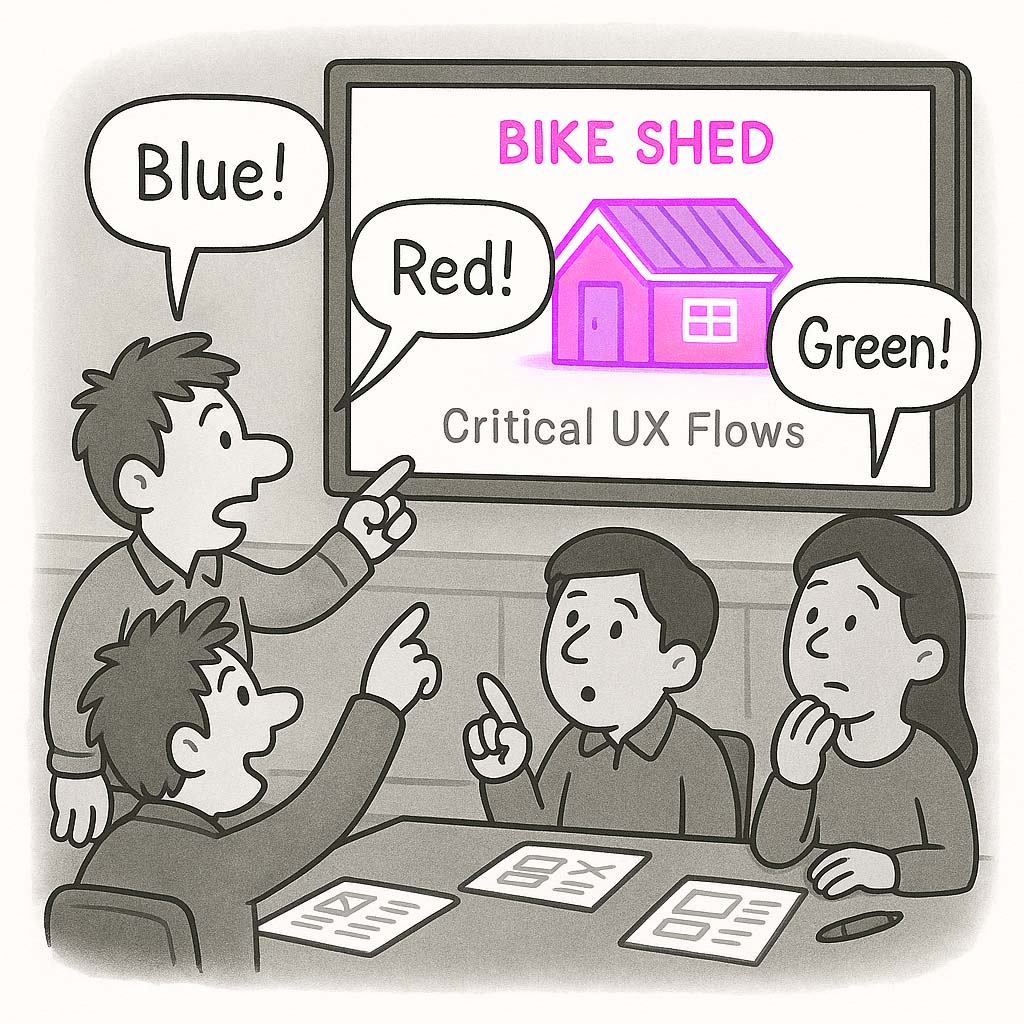

Bike shedding refers to the tendency of teams to spend disproportionate more time and energy debating trivial or easy-to-understand aspects of a project, while neglecting the more complex, impactful issues. This often happens when teams lose sight of the bigger picture goal.

ORIGIN

The UX metaphor “bike shedding” originates from C. Northcote Parkinson’s 1957 book, “Parkinson’s Law,” and specifically from his “Law of Triviality”. This law posits that the amount of time spent discussing an issue is inversely proportional to its complexity.

WHEN

Bike shedding happens when a group spends disproportionate time debating minor, easy-to-understand details while ignoring more complex, impactful problems. In UX, it shows up when a design critique turns into a long discussion about button colors, while the flawed user flow gets no attention.

You’ll most often encounter bike shedding in the following situations:

- Stakeholder reviews, where everyone feels compelled to contribute.

- Design critiques when visual tweaks are easy to discuss.

- Planning meetings when bigger issues feel too daunting to tackle.

- Cross-functional collaboration, where differing expertise levels skew the conversation toward what’s “accessible.”

In short, people need to agree on a design but feel intimidated by the harder, more important problems.

WHY

People naturally gravitate toward what they understand. Debating whether a button should be green or blue feels safe. Critiquing an information architecture or a cognitive load issue can feel abstract, risky, or outside their expertise. Bike shedding also happens because everyone wants to feel heard and contribute, even if their feedback is about something trivial.

For designers, it’s crucial to recognize bike shedding early. It can derail progress, erode focus, and leave important decisions unmade.

HOW

Here are ways to handle bike shedding effectively:

- Set clear objectives. Frame feedback sessions around the most critical user goals and business outcomes.

- Time-box minor topics. Allocate a few minutes to colors or icons, then move on.

- Facilitate the discussion. Gently redirect when the conversation veers off into trivialities.

- Show the bigger picture. Use data, flows, or research findings to keep focus on the user’s experience.

- Defer if necessary. Park trivial items in a “later” list to resolve outside the meeting.

By being intentional about framing and facilitation, you can keep the team focused on what matters most to the user.

PRO TIP

Next time you sense a bike shed discussion starting, ask: “How does this decision affect the user’s ability to achieve their goal?” If nobody can answer, it’s probably just a bike shed.

EXAMPLES

- A stakeholder review spends 20 minutes discussing the shade of the header bar while nobody notices the broken registration flow.

- A design critique turns into a debate about which stock photo to use instead of the confusing navigation hierarchy.

- A sprint planning session devolves into whether to capitalize all the labels instead of discussing the actual usability of the form.

CONCLUSION

By recognizing bike shedding and steering the team back to high-impact decisions, you help ensure that design work truly serves users, and not just preferences about the color of the bike shed.

Also known as: Painting the bike shed • Parkinson’s Law of Triviality • Pixel peeping (in visual design) • Design by committee